FROM ‘ABSURD’ TO ‘BAD’

Exactly a year ago, I showed a series of four works collectively titled Absurd Intimacies. One of these works consisted of hundreds of biscuits made out of hand-painted air dry clay, with a single ‘bite’ in each one. The other three were variations on milk spills created using resin, which had seemingly ‘pooled’ on carpets and various items of clothing. In these spills ‘floated’ pop-coloured cereal, also made out of air dry clay.

Absurd Intimacies was shown in a group exhibition called Maybe we read too much into things, which was curated by Bad Imitation’s co-curator Berny Tan. It is apt, then, that this body of work became the conceptual and material breeding ground for the exhibition we are curating together. Absurd Intimacies appropriated familiar domestic scenes, focusing on objects that held human traces, then threw them into a space of unfamiliarity. For the exhibition, Berny wrote the following description of the series:

‘Replicate’, ‘recreate’, ‘repeated’—I had already been exploring imitative gestures in these works, and in the works that came before them. Here too was the ‘uncanny’, a shift from reality that was just slight enough to be unsettling, which would later become the cornerstone of this concept of the ‘bad imitation’.This ongoing series explores the fallacy of attempting to replicate past intimacies in the pursuit of future ones. Through the use of the domestic and unassuming, Chong recreates the traces that mark a person’s presence—a bite, a spill, clothes left crumpled on the floor—which then become vessels of lost intimacies in the absence of the human body. His chosen objects are repeated, preserved, and manufactured into strange scenes that convey an uncanny mix of desire, anxiety, and hope.

Daniel Chong, Absurd Intimacies, 2020–21. Installation views, Maybe we read too much into things, curated by Berny Tan at 72-13, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and curator. Photo by Marvin Tang.

Even so, I wouldn’t say that Absurd Intimacies was about imitation, and that I was thinking about it in those terms. Yet in conversations I have had about this series, some common references emerged, linking my works to ‘copies’. One in particular was Walter Benjamin’s idea of the ‘aura’. In his 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Benjamin discussed how a reproduction always fails to represent an artwork’s aura, defined as its “presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be”. This concept was mentioned to me time and time again, though it never felt like the right fit for Absurd Intimacies, which was neither about the aura nor the authenticity of the original objects. The works I created were, in fact, ‘bad’ replicas: the biscuits were painted the wrong colours, even too bright to be natural; the cereal pieces were oddly shaped and garishly coloured, more neon than pastel.

Strangely, however, these ‘errors’ didn’t seem to matter. What I was trying to recreate was not the object, but its associated feelings, and I was able to do so even without being entirely faithful to the original. In spite of the inaccuracies, many viewers claimed to feel a sense of childhood nostalgia upon encountering my works; it was almost as if everyone possessed memories that were, in themselves, bad imitations of the real objects. Somehow, my works seemed to invoke something like Benjamin’s ‘aura’ of the original, although I feel uncomfortable with this framing even now.

Thoughts such as these left me in a conceptual limbo, unable to fully grasp the affect I was producing with my work. This undefinable thing was equal parts compelling and frustrating, and it began to infiltrate my conversations with other artists throughout the rest of 2021. This was when I began to realise I was not alone in contending with this affect. Going by other names and explanations, it was something that a number of my peers were trying to manifest in their work, without entirely understanding it themselves.

Strangely, however, these ‘errors’ didn’t seem to matter. What I was trying to recreate was not the object, but its associated feelings, and I was able to do so even without being entirely faithful to the original. In spite of the inaccuracies, many viewers claimed to feel a sense of childhood nostalgia upon encountering my works; it was almost as if everyone possessed memories that were, in themselves, bad imitations of the real objects. Somehow, my works seemed to invoke something like Benjamin’s ‘aura’ of the original, although I feel uncomfortable with this framing even now.

Thoughts such as these left me in a conceptual limbo, unable to fully grasp the affect I was producing with my work. This undefinable thing was equal parts compelling and frustrating, and it began to infiltrate my conversations with other artists throughout the rest of 2021. This was when I began to realise I was not alone in contending with this affect. Going by other names and explanations, it was something that a number of my peers were trying to manifest in their work, without entirely understanding it themselves.

Catherine Hu, study for Twice as Far Away (Blue Tile Table). Courtesy of the artist.

Bad Imitation grew out of these months of conversations and brooding. I am thinking of the exhibition format as a chance to cast a wider net; to think through the act of and impulse to imitate across multiple works and practices. Putting together this show feels more akin to mapping the space under the folds of blankets or comparing the volumes of shadows. I am trying to find the answers to questions I never knew I needed to ask.

JUMPING INTO THE GAP

Many parts of Bad Imitation were challenging, but inviting Berny to co-curate was not one of them. One casual text later and we were already trying to deconstruct my ideas. At this time—before the project was even titled Bad Imitation—we ourselves had trouble understanding what exactly it was that we were attempting to investigate. We often used terms such as ‘replicas’, ‘reproductions’, ‘copies’, and ‘repetitions’ interchangeably, without really defining their nuances. Months later, when refining the exhibition text, we still got caught up with trying to distill terms such as ‘authenticity’, ‘faithfulness’, and ‘accuracy’.

JUMPING INTO THE GAP

Many parts of Bad Imitation were challenging, but inviting Berny to co-curate was not one of them. One casual text later and we were already trying to deconstruct my ideas. At this time—before the project was even titled Bad Imitation—we ourselves had trouble understanding what exactly it was that we were attempting to investigate. We often used terms such as ‘replicas’, ‘reproductions’, ‘copies’, and ‘repetitions’ interchangeably, without really defining their nuances. Months later, when refining the exhibition text, we still got caught up with trying to distill terms such as ‘authenticity’, ‘faithfulness’, and ‘accuracy’.

Texts with Berny, discussing the language of our exhibition write-up

Looking back now, these terms were all red herrings. What we were examining with Bad Imitation in fact goes beyond the surface-level study of ‘copying’ and ‘repeating’ as artistic strategies—strategies that many artists rely upon, in one way or another. This became more obvious to us as we went through the process of putting together the list of artists for this show. Certain types of imitation didn’t seem to work for this project; in particular, imitation that was too stiff, too cold, too technical. And certain types of imitation did, although we couldn’t really articulate the reasons beyond some shared sense that they ‘had the right feeling’. It seemed that we were making an effort to bring together practices that, in their respective acts of imitation, possessed some ability to evoke a rich emotive landscape.

Texts with Berny, discussing artists we ultimately did not include in the exhibition

It was Berny who first noted that our interest was not in the (re)produced object itself, but rather in the ‘gap’ that might be opened up by a given work, a gap between the copy and the original. We were captivated by this mysterious negative space—the site, perhaps, of that ‘rich emotive landscape’—and the copies and their originals were just bookending that space. In many ways, this reflects much of what this exhibition is about: an in-between, a place created through difference and contrast, more felt than real. With each artist we contacted, each subsequent proposal for how an artwork could operate within that ‘gap’, we inched closer to defining the blurry boundaries of what a ‘bad imitation’ is and could do.

The use of the word ‘bad’ is a sleight of hand. It sets up a duality with what is ‘good’—or original, or authentic, or faithful—but this is not our exhibition’s premise. Bad Imitation is not against perfection, nor is it wholly about failure; it is not about a lack of skill, nor does it challenge the value of art itself. ‘Bad’, in this context, is more of an intentional deviation. One could say it is a provocation, or even a joke. The word is so damning, so flattening, that it causes a recoil. It opens a space for someone to wonder why it was used at all.

And so there are in-betweens here, presented by both words in our exhibition’s title. An imitation cannot exist without its original, and its existence emphasises the distance between itself and its source material. An imitation that is deemed ‘bad’ widens that distance, without severing the connection. Calling something ‘bad’ demands an explanation for that value judgment, a negotiation of the space between ‘bad’ and ‘good’.

In thinking through the mechanics of the ‘bad imitation’, I look to the subject matter of the artworks in our exhibition. These newly commissioned works reference sources that are commonplace, domestic, everyday, known—the tableaux we observe in public spaces; the objects that surround us in our homes; the scenes we watch on television shows; the words of advice that we receive, which might well be clichés we’ve heard many times before. Even the act of breathing itself, so natural that we are hardly ever conscious of it, is ripe for a bad imitation.

THE ‘BAD’ IN BAD IMITATION

The use of the word ‘bad’ is a sleight of hand. It sets up a duality with what is ‘good’—or original, or authentic, or faithful—but this is not our exhibition’s premise. Bad Imitation is not against perfection, nor is it wholly about failure; it is not about a lack of skill, nor does it challenge the value of art itself. ‘Bad’, in this context, is more of an intentional deviation. One could say it is a provocation, or even a joke. The word is so damning, so flattening, that it causes a recoil. It opens a space for someone to wonder why it was used at all.

And so there are in-betweens here, presented by both words in our exhibition’s title. An imitation cannot exist without its original, and its existence emphasises the distance between itself and its source material. An imitation that is deemed ‘bad’ widens that distance, without severing the connection. Calling something ‘bad’ demands an explanation for that value judgment, a negotiation of the space between ‘bad’ and ‘good’.

In thinking through the mechanics of the ‘bad imitation’, I look to the subject matter of the artworks in our exhibition. These newly commissioned works reference sources that are commonplace, domestic, everyday, known—the tableaux we observe in public spaces; the objects that surround us in our homes; the scenes we watch on television shows; the words of advice that we receive, which might well be clichés we’ve heard many times before. Even the act of breathing itself, so natural that we are hardly ever conscious of it, is ripe for a bad imitation.

Khairullah Rahim x Nghia Phung, reference image for after-party. Courtesy of the artists.

Pat Toh, studies for Air Ways. Courtesy of the artist.

Pat Toh, studies for Air Ways. Courtesy of the artist.

While varying in form, the accessibility of these ‘originals’ is no surprise. A bad imitation cannot exist if its viewers have no sense of its original; no capacity to decide if it is ‘bad’ at all. The more relatable and familiar the original, the more material can be created with an imitation’s differences. Something strange must occur: a bad imitation must hold on to enough of its original, must create some image, or feeling, or sense of the original, and at the same time say, “I am not like that thing”. This isn’t to say that the works don’t work if one doesn’t know what they are referencing. It is only to say that they work differently if you do.

INFILTRATING THE ORIGINAL

The ‘bad imitation’ is thus not defined by its aesthetic, but rather by a process of latching onto, then departing from the original. The artist then slips their intentions into the space of difference generated by this departure. This gap is not physically represented by the object, but rather conjured in our perception. It is created by the artist, and finished in the mind of the viewer.

INFILTRATING THE ORIGINAL

The ‘bad imitation’ is thus not defined by its aesthetic, but rather by a process of latching onto, then departing from the original. The artist then slips their intentions into the space of difference generated by this departure. This gap is not physically represented by the object, but rather conjured in our perception. It is created by the artist, and finished in the mind of the viewer.

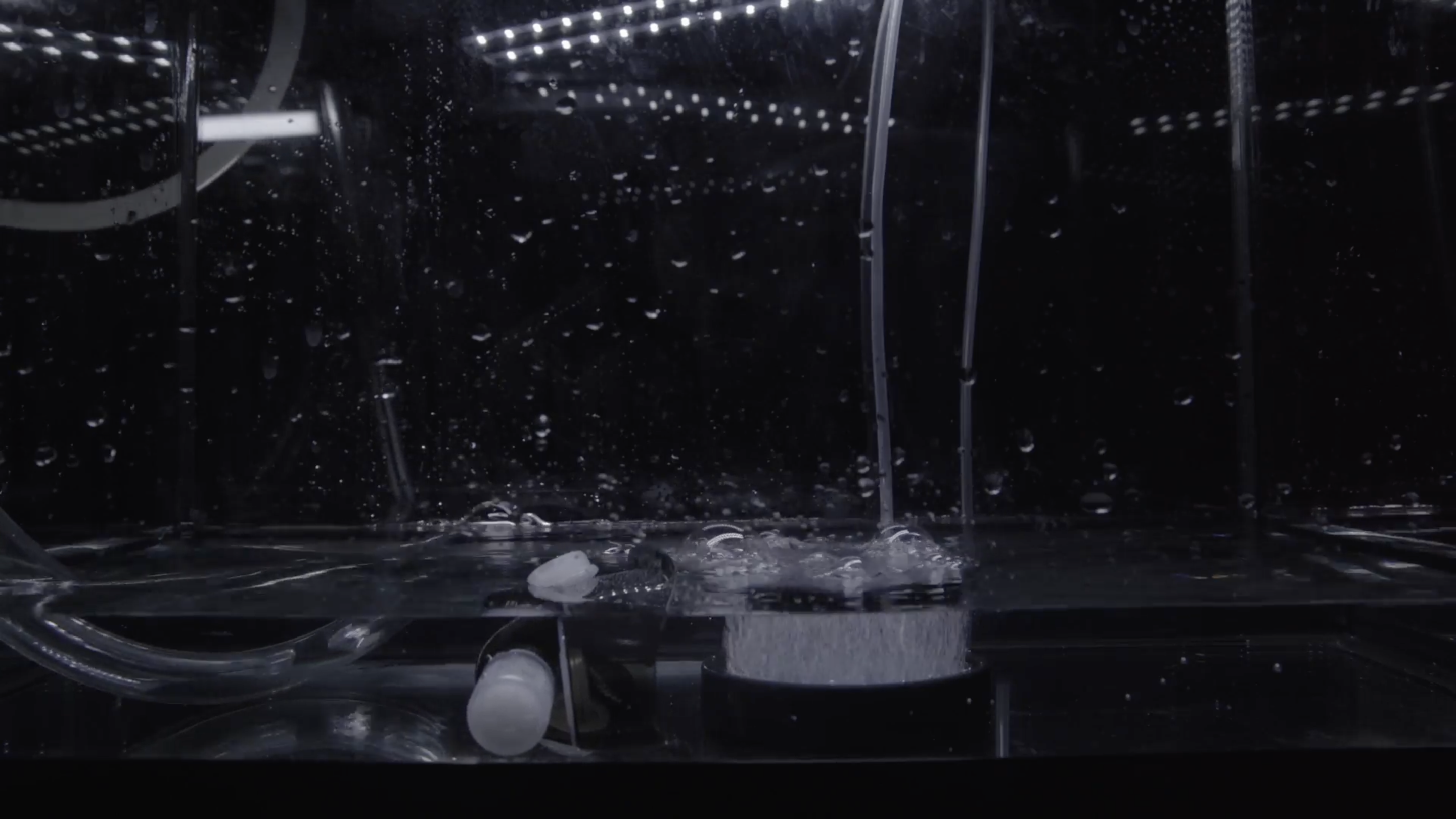

Moses Tan, still from A whispering of salt. Courtesy of the artist.

Ashley Hi, GAN-produced test images for Cable Imgs. Courtesy of the artist.

Ashley Hi, GAN-produced test images for Cable Imgs. Courtesy of the artist.

You could call this something insidious, like an infiltration; but it is also something more nebulous, like an absorption. Whichever it is, I think of it as more generative than destructive. I imagine an imitation squeezing into the spaces the original has failed to occupy, and expanding them. For a ‘bad imitation’ is not ‘badly done’; it does not destroy its connections to the original by failing to represent it at all. A ‘bad imitation’ done well, is one that possesses a form of uncanniness, which lingers and tints the viewer’s perception of the source material. It locates the mental space that the original occupies in the viewer’s mind, then stays there, even after the viewer leaves the exhibition. This is what a good ‘bad imitation’ does—it becomes part of the original.

And so, as you walk through Bad Imitation, I recommend sitting with these works and trying to look at them in two ways. First, pretend you have no idea what each work is referencing. Then, actively compare it to its original. Think about how these imitations deviate from their source, but more importantly, note what these deviations do to you as a viewer. Perhaps when you next encounter the original, outside of the exhibition space, you will instead think of that time when you saw its bad imitation.

And so, as you walk through Bad Imitation, I recommend sitting with these works and trying to look at them in two ways. First, pretend you have no idea what each work is referencing. Then, actively compare it to its original. Think about how these imitations deviate from their source, but more importantly, note what these deviations do to you as a viewer. Perhaps when you next encounter the original, outside of the exhibition space, you will instead think of that time when you saw its bad imitation.

Editor’s Note

by Berny TanI was meant to write a curatorial note of my own, to be paired with Daniel’s. I had even started composing an outline in my head. I would first discuss patterns of behaviour that we subconsciously develop over the course of our lives, and how those patterns might have roots in our childhood experiences—in our ‘imitations’ of the adults who brought us up, who were in turn imitating the adults who raised them. I would mention how, if we are lucky enough to develop an awareness of these patterns, we might learn how to reinforce the good and reorient the bad. Then, I would lead into how artists constantly return to similar ways of working, similar subjects; grapple with them again and again, although they might approach them a little differently each time. I would have talked, too, about how a curator might loop back to similar (types of) artists and artworks across different projects. Eventually, I would meditate on whether we are always aiming for—not just bad imitations, but worse ones. I mean that in the sense that as we grow and learn, we keep trying to do better, to build on but also distinguish ourselves from what came before.

Or something along those lines.

It would have been an interesting enough text, I think, if I could have pulled it off. Instead, I have chosen to let Daniel’s words represent this exhibition we have curated together. Well, perhaps it isn’t entirely accurate to say “Daniel’s words”. While Daniel wrote the original version, he gave me leeway afterwards to tease out and clarify his ideas. He didn’t mind that I took some artistic licence, and integrated some of my own style of prose into his essay. I rephrased entire sentences; replaced more than a few words; elaborated on his statements in ways that didn’t bother to emulate Daniel’s style. I have never been so aggressive in my editing, nor has a text written by somebody else ever taken me this long to work through. So there is quite a lot of myself in the essay, in fact; things I can’t imagine Daniel saying or writing. He was very generous in giving me space for this indulgence. (He would tell me, later, that seeing the essay evolve in my hands was like watching a ‘live’ bad imitation.)

Despite the liberties I took with his essay, it doesn’t feel right to say it was co-written by us. The text still belongs to Daniel; my role was simply to better articulate what Daniel meant to convey, and to do so in a way that remains true to the thought processes that underpinned this exhibition. Since Bad Imitation grew out of Daniel’s practice, it felt right for his ideas to be foregrounded. As a curator, I don’t know if I would have come up with anything like Bad Imitation on my own. I think this exhibition could have existed, in some form, without me, but it would not have existed without Daniel.

Michael Lee, Not Artistic Advice (detail), 2022. Badge buttons with print on paper, matte lamination and pin backing, 3.8 x 3.8 cm each. Image courtesy of the artist.

I have been wondering if I am not so much co-curating an exhibition with Daniel, as much as curating Daniel curating an exhibition. His curatorial projects often begin as extensions of the ideas in his art practice; the exhibition form is a methodology for him to better understand those ideas, and how they emerge in different ways in practices beyond his own. Though I am deeply involved in Bad Imitation, as deeply as I am with any of my personal curatorial projects, I’ve also felt a certain distance from it. Not in a bad way—not in the way of not feeling ownership over the exhibition—but I understand that I am here, in part, to shape the arena for Daniel’s ideas to flourish.

Nonetheless, I view this essay as a joint effort, representative of our collaborative style of curating. It is a partnership built on mutual support and inherent trust. It’s the sort of trust you’d have to have in someone to allow them to take apart your writing, then put it back together again, knowing that it would still be recognisable as yours. It means I can send Daniel a text like this:

Nonetheless, I view this essay as a joint effort, representative of our collaborative style of curating. It is a partnership built on mutual support and inherent trust. It’s the sort of trust you’d have to have in someone to allow them to take apart your writing, then put it back together again, knowing that it would still be recognisable as yours. It means I can send Daniel a text like this:

i feel like i’m ship of theseusing1 your essay

i’m like replacing the words but trying to retain its essence

and he will respond not with frustration or offence, but with:

Somehow apt

But omg hahahaha

1 The Ship of Theseus is a thought experiment in Western philosophy. It raises the question of whether an object that has had all of its components replaced—such as a ship whose wooden parts decayed over time—remains fundamentally the same object.

Biography

Daniel Chong (b. 1995, Singapore) is an artist-curator whose curatorial approach grows from the curiosities within his artistic practice. Drawing from the often uncanny nature of affect, his projects read as extended artistic experiments within the loose framework of an exhibition. Independently, he has curated Melting! Melting! (2019) at Gillman Barracks and RAID (2016) at Tiong Bahru Air Raid Shelter. He was also Assistant Curator of the non-profit arts organisation OH! Open House from 2019 to 2021.

Biography