Title

Unintended vessels

Year

2022

Medium

Cut plastic storage boxes, used clothes, stuffed toys, resin, silicone

Dimensions

Dimensions variable

Unintended vessels

Year

2022

Medium

Cut plastic storage boxes, used clothes, stuffed toys, resin, silicone

Dimensions

Dimensions variable

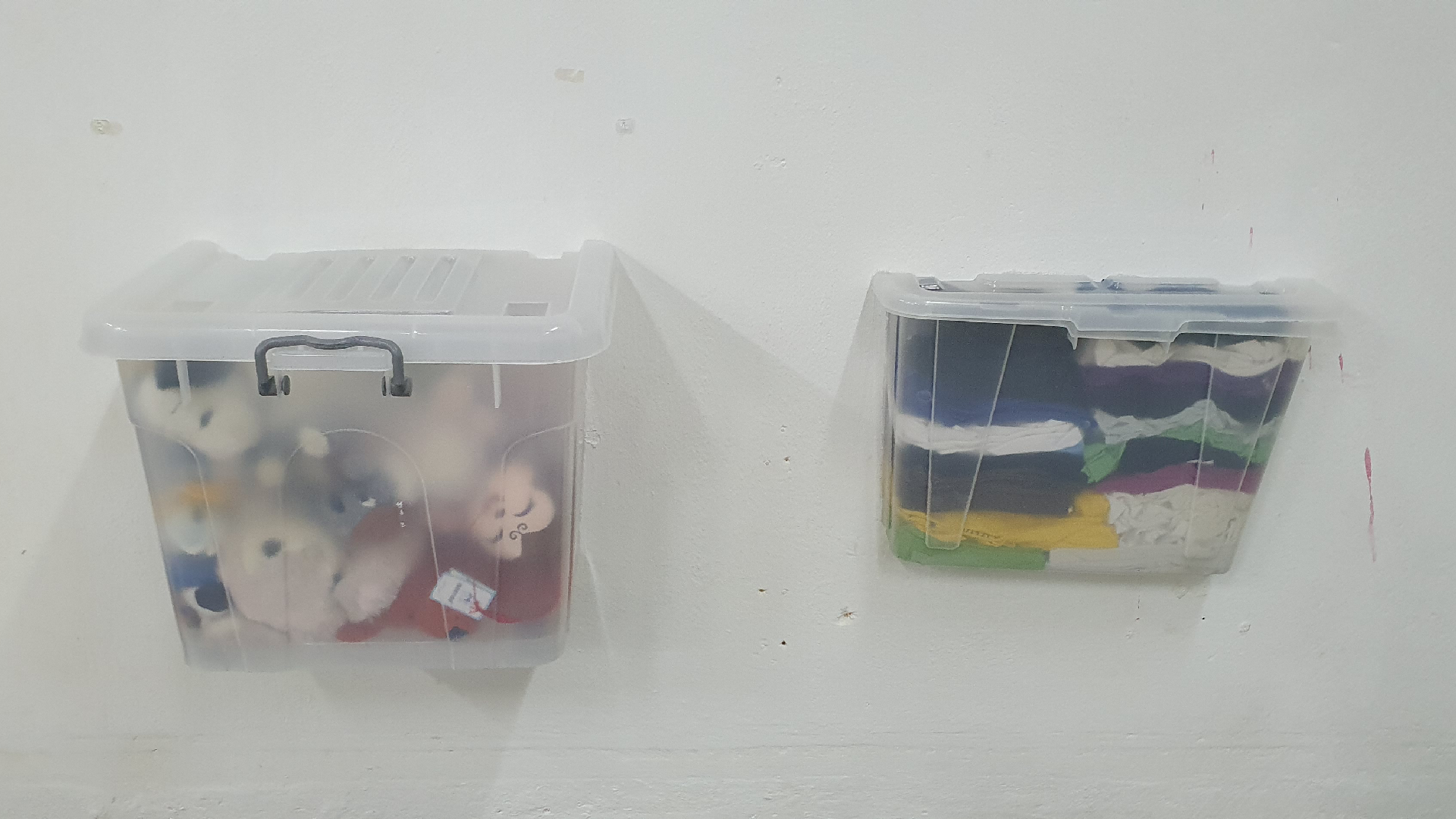

This series of sculptures centres the unassuming plastic storage box as an unexpected mnemonic device. On its face an entirely utilitarian and forgettable object, this everyday vessel somehow manages to become a conduit for poignant domesticity—a reminder of the little-used, sometimes sentimental possessions that have been neatly packed in similar boxes in our homes.

In this installation, the boxes are filled with clothes, toys, and memorabilia, organised and repeated, all pressing against the translucent plastic as if suspended in a fog. Stranger still, they appear to be emerging, or perhaps receding into, the floors and the walls of the exhibition space. These surreal vitrines thus exist in a strange limbo between functionality and sentimentality, uncannily standing in for the things we hold onto, yet put away; rarely use, yet cannot bear to discard; wish to keep out of sight, yet might one day choose to revisit.

In this installation, the boxes are filled with clothes, toys, and memorabilia, organised and repeated, all pressing against the translucent plastic as if suspended in a fog. Stranger still, they appear to be emerging, or perhaps receding into, the floors and the walls of the exhibition space. These surreal vitrines thus exist in a strange limbo between functionality and sentimentality, uncannily standing in for the things we hold onto, yet put away; rarely use, yet cannot bear to discard; wish to keep out of sight, yet might one day choose to revisit.

Interview with the artist

Q Berny Tan

In recent years, you’ve moved away from using found objects as they are, and instead manipulate them, or even fabricate objects outright. Why this transition?

This might seem counterintuitive, but this transition has allowed me to achieve a greater sense of reality in my works. I realised that people often remember things wrongly, in the sense that our perception and memories of objects are always more perfect than reality. Take for example the biscuit replicas I had made in my earlier series Absurd Intimacies—no one noticed that the colours were entirely wrong, and many even mis-remembered the brands of some of the biscuits. It was around then that it dawned on me that people don’t always know what they know, but instead have more of a connotative field of objects that they amalgamate over a period of time.

By using found objects on their own, I cannot tap into that connotative subconscious that people have of said object. It's almost as if the real object is the bad imitation. The process of manipulation and fabrication gives me more room to play with the psychological image of the object, and to think of its materiality in terms of conceptual connotations rather than faithfulness to physical appearance.

By using found objects on their own, I cannot tap into that connotative subconscious that people have of said object. It's almost as if the real object is the bad imitation. The process of manipulation and fabrication gives me more room to play with the psychological image of the object, and to think of its materiality in terms of conceptual connotations rather than faithfulness to physical appearance.

This series began initially with your interest in the plastic storage box. Could you explain why this object has captivated you?

The plastic storage box is an everyday object with so much potential. It recedes into the background, yet is ever-present as a vessel to hold objects. In particular, it is used to store things that are only used occasionally, or that don’t serve a practical function, but are still kept for sentimental reasons. So, the phenomenology of the box is never just about the box itself, but what it holds. It is this strange connotative puzzle—a not-quite-standalone object that is always remembered and seen as being filled or used. Its function constitutes its appearance, and our experience of it.

In thinking about this object, I keenly felt the paradox of everyday aesthetics that permeates my practice. In exalting or presenting the everyday in an exhibitionary context, it betrays the setting in which it is experienced. My interest in the box eventually evolved into an attempt to overcome this paradox between function and aesthetics. As an object, it is deceptively easy to work with—almost too perfect as a metaphor to talk about quiet domestic spaces, while also being a literal vessel with both interior and exterior spaces that I could play with. Yet, it resists artistic intervention, unless I go to the extent of entirely effacing it. In that case, any other box or molten plastic would suffice, rendering the materiality of the plastic storage box pointless. On the other hand, leaving it too unaltered makes it too utilitarian in its affect, which would jolt it out of the art space and context. This unassuming box thus became both my bane and my muse, as I sought to balance all these connotations.

In thinking about this object, I keenly felt the paradox of everyday aesthetics that permeates my practice. In exalting or presenting the everyday in an exhibitionary context, it betrays the setting in which it is experienced. My interest in the box eventually evolved into an attempt to overcome this paradox between function and aesthetics. As an object, it is deceptively easy to work with—almost too perfect as a metaphor to talk about quiet domestic spaces, while also being a literal vessel with both interior and exterior spaces that I could play with. Yet, it resists artistic intervention, unless I go to the extent of entirely effacing it. In that case, any other box or molten plastic would suffice, rendering the materiality of the plastic storage box pointless. On the other hand, leaving it too unaltered makes it too utilitarian in its affect, which would jolt it out of the art space and context. This unassuming box thus became both my bane and my muse, as I sought to balance all these connotations.

The tableaux that you create in your installations often present the domestic intersecting with the surreal. What about this combination is so compelling for you?

I don’t actually view it as a combination, but rather a kind of inception. I’ve always been trying to tap into the vernacular, domestic space, be it in presentation or materiality. It’s such a ripe area to work with: it is both an important part of our daily lived experiences, yet it functions so monotonously, and efficiently, that it disappears. While not epic nor grand, the domestic affects us quite insidiously. I see my work as almost hijacking this space, rewiring the connotative possibilities for the viewer, so that the next time they see or use said object, my intervention slips in there as well. I constantly ask myself how I can affix small affective textures onto the objects we already use, so that I can slightly displace, lay atop, skim, or shift ever so gently the gradients of the viewer’s everyday experiences.

This is why my works are always integrated into their surrounding spaces—almost eliminating the boundaries they have with the viewer—yet also sit very squarely in a kind of altered reality, a space that is uncanny yet plausibly real. This inception is stretched just enough that the work isn’t entirely removed from its original references, allowing the viewer to dwell with the object and its extended emotive surfaces.

This is why my works are always integrated into their surrounding spaces—almost eliminating the boundaries they have with the viewer—yet also sit very squarely in a kind of altered reality, a space that is uncanny yet plausibly real. This inception is stretched just enough that the work isn’t entirely removed from its original references, allowing the viewer to dwell with the object and its extended emotive surfaces.

Biography