This essay is one of three texts commissioned for this exhibition, discussing ‘bad imitations’ in disciplines beyond visual art.

Early experimentations in telematic arts1 have enabled networked exchanges across borders through telecommunication technology, spurring conversations about collaboration and art-making outside traditional presentation spaces. In the first presentations of E.A.T.’s Telex: Q&A, telex machines connected participants in New York, Ahmedabad, Tokyo and Stockholm as they engaged in question-and-answer exchanges about the future.

This was 1971.

50 years on, telematic performance has saturated the theatre world in legions of formats. Far from the networked creativity it offered in its ancestry, it became a necessity that housed the complete decentralisation of theatre and displacement of the spectator as the world migrated online in response to COVID-19 border lockdowns.

This was 1971.

50 years on, telematic performance has saturated the theatre world in legions of formats. Far from the networked creativity it offered in its ancestry, it became a necessity that housed the complete decentralisation of theatre and displacement of the spectator as the world migrated online in response to COVID-19 border lockdowns.

1 Telematic arts involve the use of networked communications as a medium for technologically-mediated artistic encounters.

FROM STAGE TO SCREEN

Theatre has always been an art of imitation. In this mass shift to the digital, during which large populations came face-to-face with new, extended realities on screen, the industry’s collective response converged on a central question of whether theatre can find new life in different forms.

The need for two-way communication tools to connect remotely saw a new wave of pandemic performance staged via Zoom, WhatsApp, and streaming sites, among many others. But can a form that imitates be imitated in digital spaces?

Beginning attempts to answer this question included dramatised readings like Fezhah Maznan/Teater Ekamatra’s Baca Skrip: #_ and Zoom adaptations like How Drama’s Fat Kids Are Harder to Kidnap On Zoom, both of which used multipanel video conferencing interfaces to situate different actors together onscreen. These presentations largely retained traditional performer-spectator relationships, but the fragmented nature of remote participation and spectatorship quickly drew attention to the complex paradigms of the cyberstage. Where once was a live body now lies its mediated self, and what once was received by spectators in the ‘here and now’ is now one step removed—separated by the screen’s tangible fourth wall.

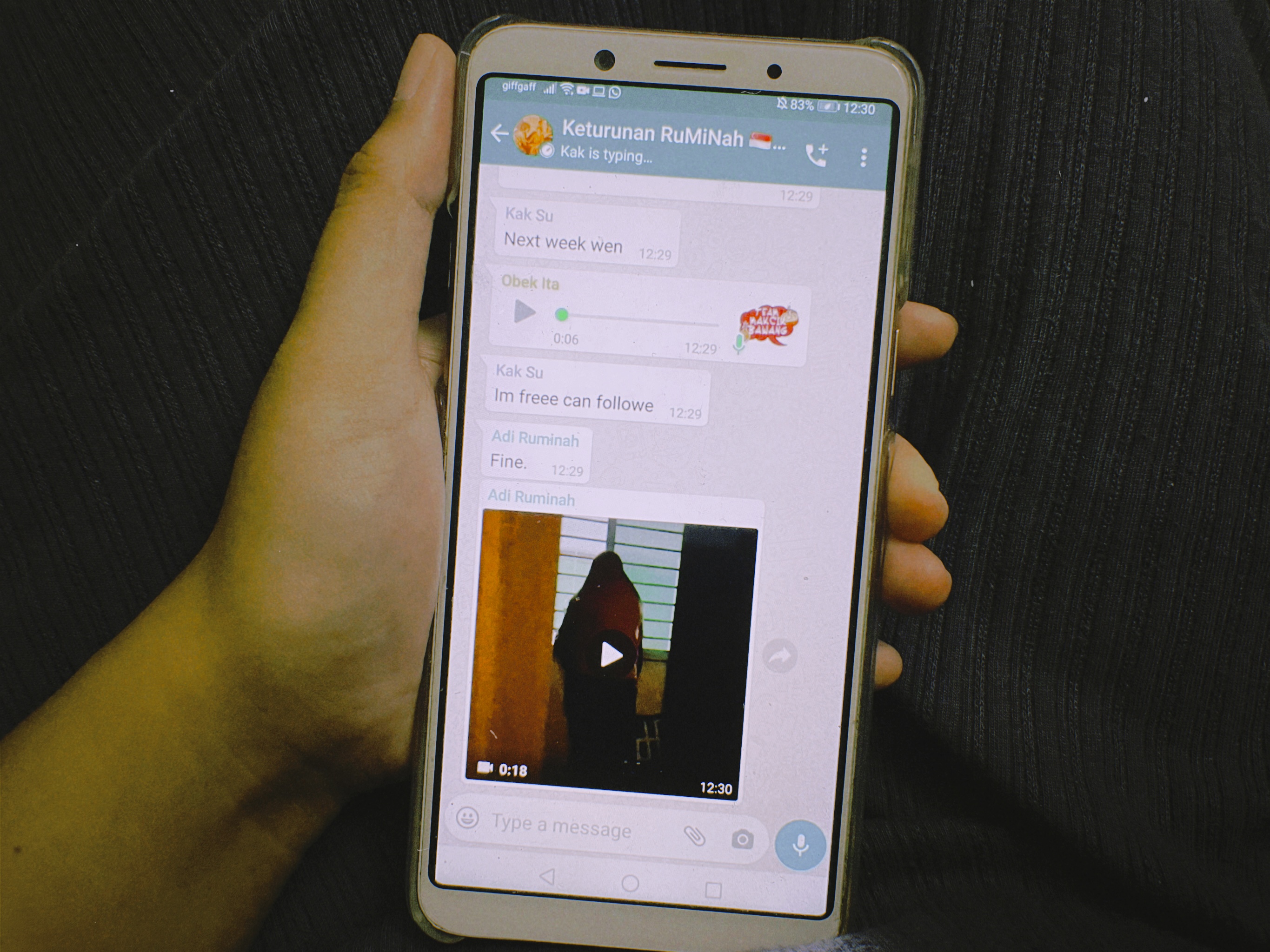

Podcasts like Lepak One Korner’s The Podcast and WhatsApp dramas like Hatch Theatrics’ Keturunan Ruminah diverged from these stagings by removing performers’ bodies entirely, instead conveying drama purely through voice or text. More experimental iterations like DARKFIELD’s immersive radio play, Double, used binaural sound to create aural pictures of the performance within spectators’ own homes, while NIGHTCAP’s Handle with Care turned to snail mail to literally deliver performance to spectators’ doorsteps. While these works leapfrogged the fourth wall altogether and delivered personalised experiences to individual spectators in real time, it also made the experience a solitary one that cannot replicate the communality of live spectatorship.

The need for two-way communication tools to connect remotely saw a new wave of pandemic performance staged via Zoom, WhatsApp, and streaming sites, among many others. But can a form that imitates be imitated in digital spaces?

Beginning attempts to answer this question included dramatised readings like Fezhah Maznan/Teater Ekamatra’s Baca Skrip: #_ and Zoom adaptations like How Drama’s Fat Kids Are Harder to Kidnap On Zoom, both of which used multipanel video conferencing interfaces to situate different actors together onscreen. These presentations largely retained traditional performer-spectator relationships, but the fragmented nature of remote participation and spectatorship quickly drew attention to the complex paradigms of the cyberstage. Where once was a live body now lies its mediated self, and what once was received by spectators in the ‘here and now’ is now one step removed—separated by the screen’s tangible fourth wall.

Podcasts like Lepak One Korner’s The Podcast and WhatsApp dramas like Hatch Theatrics’ Keturunan Ruminah diverged from these stagings by removing performers’ bodies entirely, instead conveying drama purely through voice or text. More experimental iterations like DARKFIELD’s immersive radio play, Double, used binaural sound to create aural pictures of the performance within spectators’ own homes, while NIGHTCAP’s Handle with Care turned to snail mail to literally deliver performance to spectators’ doorsteps. While these works leapfrogged the fourth wall altogether and delivered personalised experiences to individual spectators in real time, it also made the experience a solitary one that cannot replicate the communality of live spectatorship.

Local theatre companies such as Hatch Theatrics turned to communication tools like WhatsApp to create innovative digital presentations that diverge from traditional theatre stagings. (Courtesy of Hatch Theatrics.)

ONLINE SCENOGRAPHY AND DIGITAL PLACEMAKING

It has been continually debated that the absence of live presence makes pandemic performance only a shadow of what it attempts to imitate. These debates were fuelled by unfulfilled hunger for physical closeness and intimacy, heightened by long periods of isolation from multiple lockdowns.

If theatre mirrors reality, then pandemic performance strived to mask our new realities. As many began to experience screen fatigue months into the pandemic, online scenography emerged as a dramaturgical strategy for distraction and escapism. Cyberstages, for instance, were transformed into performance worlds using presentation tools like virtual backgrounds and filters. In Sim Yan Ying’s Where Are You? (Digital), individual Zoom video panels presented different performers’ accounts of grief via curated montages of visual fragments that were unified with coloured lighting and filters. The scenographic storytelling reflected the universality of these accounts, but also the tragedy of having to undergo these experiences in isolation.

The blended medialities of live, prerecorded, and virtual within a single frame blur distinctions between ‘performance reality’ and ‘pandemic reality’, creating a sense of place that transports spectators into the performance world. This opened doors for festivals like StoryFest, STRIKE! Digital Festival, and RUMAHfest to find platforms for curation and festival placemaking online.

RUMAHfest, in particular, began as a one-day festival to open up spaces for integration amongst London-based Asian artists. As racially-motivated attacks in London increased mid-pandemic and widespread disease threatened individuals’ safety, the festival moved online and became an important site for Asian artists and spectators to participate in masses. The specially-curated platform hosted in real time not only blended geographical borders and encouraged cultural contact, but also turned the festival into an accessible site for cultural and sociopolitical movement and expression.

If theatre mirrors reality, then pandemic performance strived to mask our new realities. As many began to experience screen fatigue months into the pandemic, online scenography emerged as a dramaturgical strategy for distraction and escapism. Cyberstages, for instance, were transformed into performance worlds using presentation tools like virtual backgrounds and filters. In Sim Yan Ying’s Where Are You? (Digital), individual Zoom video panels presented different performers’ accounts of grief via curated montages of visual fragments that were unified with coloured lighting and filters. The scenographic storytelling reflected the universality of these accounts, but also the tragedy of having to undergo these experiences in isolation.

The blended medialities of live, prerecorded, and virtual within a single frame blur distinctions between ‘performance reality’ and ‘pandemic reality’, creating a sense of place that transports spectators into the performance world. This opened doors for festivals like StoryFest, STRIKE! Digital Festival, and RUMAHfest to find platforms for curation and festival placemaking online.

RUMAHfest, in particular, began as a one-day festival to open up spaces for integration amongst London-based Asian artists. As racially-motivated attacks in London increased mid-pandemic and widespread disease threatened individuals’ safety, the festival moved online and became an important site for Asian artists and spectators to participate in masses. The specially-curated platform hosted in real time not only blended geographical borders and encouraged cultural contact, but also turned the festival into an accessible site for cultural and sociopolitical movement and expression.

Beyond providing a safe space for mass gatherings, festivals like RUMAHfest were important sites for cultural and sociopolitical expression. (Courtesy of RUMAH.)

THE POLITICS OF IMITATION IN THE DIGITAL

While technology is borderless, it is not boundaryless. In Bhumi Collective’s digital adaptation of Charlie, individual participants are invited to a 15-minute one-on-one Zoom encounter with the 12-year old eponymous character—played by an adult performer—who has never encountered the world outside the four walls of her room. The participatory performance, in its live and digital presentations, challenged participants to describe the world we live in, by framing these interactions through the lens of an adolescent who believes that danger exists beyond her isolation.

Charlie’s original live staging placed performer and participant within the same space, physically and consensually. Unlike its live counterpart, the Zoom adaptation resonated with spectators who themselves were isolated at home mid-pandemic. But in light of rising security risks around video conferencing platforms and warnings against online predators2, the ontological concerns explored in this work also brought attention to an often-overlooked issue surrounding ethics and consent in this new virtual landscape.

The very nature of technology invites interactivity and participation—more so, perhaps, than customarily expected in traditional theatre stagings—and it thus comes enmeshed with ethical concerns and obligations. The presence of web cameras transforms passive spectatorship into active voyeurism; screens reduce live bodies into virtual mediations of the original; the conjoined remote space between performer and spectator blurs the lines between private-and-public and virtual-and-actual. When we consent to entering virtual spaces of interactivity and participation, the extent of our consent becomes uncertain, as the parameters between the performance, the virtual, and the ‘real’ are no longer so clear.

How much agency, then, do remote spectators have compared to live spectators, and where does this agency lie? The rise of ‘Zoom theatre’ has created a culture of invitation where moderators can exercise greater control over participants entering and leaving the space. This has allowed artists to manage participants in spaces, minimise, or even eliminate mid-show disruptions, and offer ticketed shows online. At the same time, it also creates artificial borders within what is generally considered a ‘borderless’ internet. These artificial borders at its minimum can create closed spaces for private discussions and safe dialogues, but at its extremes, can pose a danger of selective or even discriminatory spectator management.

In addition, spectators do not retain complete control over their participation, mics and cameras. Next to traditional theatre’s passive spectatorship, this has the potential to subvert expectations on how we conventionally practice and enforce traditional theatre etiquette. However, the artificiality of it brings attention to how we consciously, or subconsciously, implicate others in the systems and structures of the cyberstage.

Charlie’s original live staging placed performer and participant within the same space, physically and consensually. Unlike its live counterpart, the Zoom adaptation resonated with spectators who themselves were isolated at home mid-pandemic. But in light of rising security risks around video conferencing platforms and warnings against online predators2, the ontological concerns explored in this work also brought attention to an often-overlooked issue surrounding ethics and consent in this new virtual landscape.

The very nature of technology invites interactivity and participation—more so, perhaps, than customarily expected in traditional theatre stagings—and it thus comes enmeshed with ethical concerns and obligations. The presence of web cameras transforms passive spectatorship into active voyeurism; screens reduce live bodies into virtual mediations of the original; the conjoined remote space between performer and spectator blurs the lines between private-and-public and virtual-and-actual. When we consent to entering virtual spaces of interactivity and participation, the extent of our consent becomes uncertain, as the parameters between the performance, the virtual, and the ‘real’ are no longer so clear.

How much agency, then, do remote spectators have compared to live spectators, and where does this agency lie? The rise of ‘Zoom theatre’ has created a culture of invitation where moderators can exercise greater control over participants entering and leaving the space. This has allowed artists to manage participants in spaces, minimise, or even eliminate mid-show disruptions, and offer ticketed shows online. At the same time, it also creates artificial borders within what is generally considered a ‘borderless’ internet. These artificial borders at its minimum can create closed spaces for private discussions and safe dialogues, but at its extremes, can pose a danger of selective or even discriminatory spectator management.

In addition, spectators do not retain complete control over their participation, mics and cameras. Next to traditional theatre’s passive spectatorship, this has the potential to subvert expectations on how we conventionally practice and enforce traditional theatre etiquette. However, the artificiality of it brings attention to how we consciously, or subconsciously, implicate others in the systems and structures of the cyberstage.

2 Hariz Baharudin, “Coronavirus: No more Zoom for home-based learning after hackers show obscene photos to Singapore students,” The Straits Times, April 10, 2020.

WHAT MAKES THEATRE, THEATRE

In writing about pandemic performance and the (in)imitability of theatre, I curated a selection of examples that I felt best showcased the theatre industry’s breadth of work and diversity of genres on the cyberstage. From small-scale participatory performances to large, citywide festivals, these works presented theatre’s resistance to disappearance, and its coup de théâtre in face of challenging times.

As a spectator, I view these works as an attempt to collectively make sense of new realities while staying connected, finding escape, and retaining a sense of normalcy. As a theatre-maker, the advent of the digital is a call for reflection on the way we conventionally collaborate and devise performance—how we select performance tools; how we define performance languages; how we consider the systems and structures of the space in our processes; how we invite the audience in; and how we assess and review ethical considerations that may have been overlooked along the way.

As a spectator, I view these works as an attempt to collectively make sense of new realities while staying connected, finding escape, and retaining a sense of normalcy. As a theatre-maker, the advent of the digital is a call for reflection on the way we conventionally collaborate and devise performance—how we select performance tools; how we define performance languages; how we consider the systems and structures of the space in our processes; how we invite the audience in; and how we assess and review ethical considerations that may have been overlooked along the way.

The advent of the digital is a call for reflection on the way theatre artists collaborate and devise performance. (Courtesy of Faezah Zulkifli.)

Relationships between performer, spectator, and space will continue to shift as theatre moves with the times. In the 1970s, when telecommunication technology was not as widespread, emphasis was placed on connecting cultures across physical borders. Today, pandemic performances not only diverge in their attempt to recreate theatre online and keep an art form alive in challenging times, but they also produce a kind of theatre that redefines and restructures the way we conventionally understand performance—including the historical baggage and expectations traditional theatre carries with it.

As the industry shifts towards a future in the digital, how much of these structures do we retain? What do we choose to redefine? And what should we let go of? The crux of theatre has long been its liveness, ephemerality, and communality, all of which are challenged by the conditions of pandemic performance. But perhaps, in the same ways that stage configurations and performer-spectator relations have leaned into change, pandemic performance can also reimagine the way we view liveness, how we rediscover communal experiences, and where ephemerality lies on the cyberstage.

As the industry shifts towards a future in the digital, how much of these structures do we retain? What do we choose to redefine? And what should we let go of? The crux of theatre has long been its liveness, ephemerality, and communality, all of which are challenged by the conditions of pandemic performance. But perhaps, in the same ways that stage configurations and performer-spectator relations have leaned into change, pandemic performance can also reimagine the way we view liveness, how we rediscover communal experiences, and where ephemerality lies on the cyberstage.

Biography

Faezah Zulkifli is a theatre-maker in new theatre practices and technologies. Her work examines the intersections between theatre and technology, particularly the dramaturgy of new media and the politics of the digital in collaborative theatre practice. Faezah has trained under leading artists at the forefront of theatre and technology, including DARKFIELD, Dead Centre, and CREW. She was also an associate artist of London-based multimedia performance company ‘PUNKT from 2018–2019. Her work in theatre research has been Highly Commended and published at The Global UA, where she was also awarded Regional Winner for Asia for the Music, Film, and Theatre category in 2017. She holds an MA (Dist) in Advanced Theatre Practice from the Royal Central School of Speech & Drama, and a BA (Hons) in English from Nanyang Technological University.

Follow

Instagram