Title

A whispering of salt

Year

2021 – 22

Medium

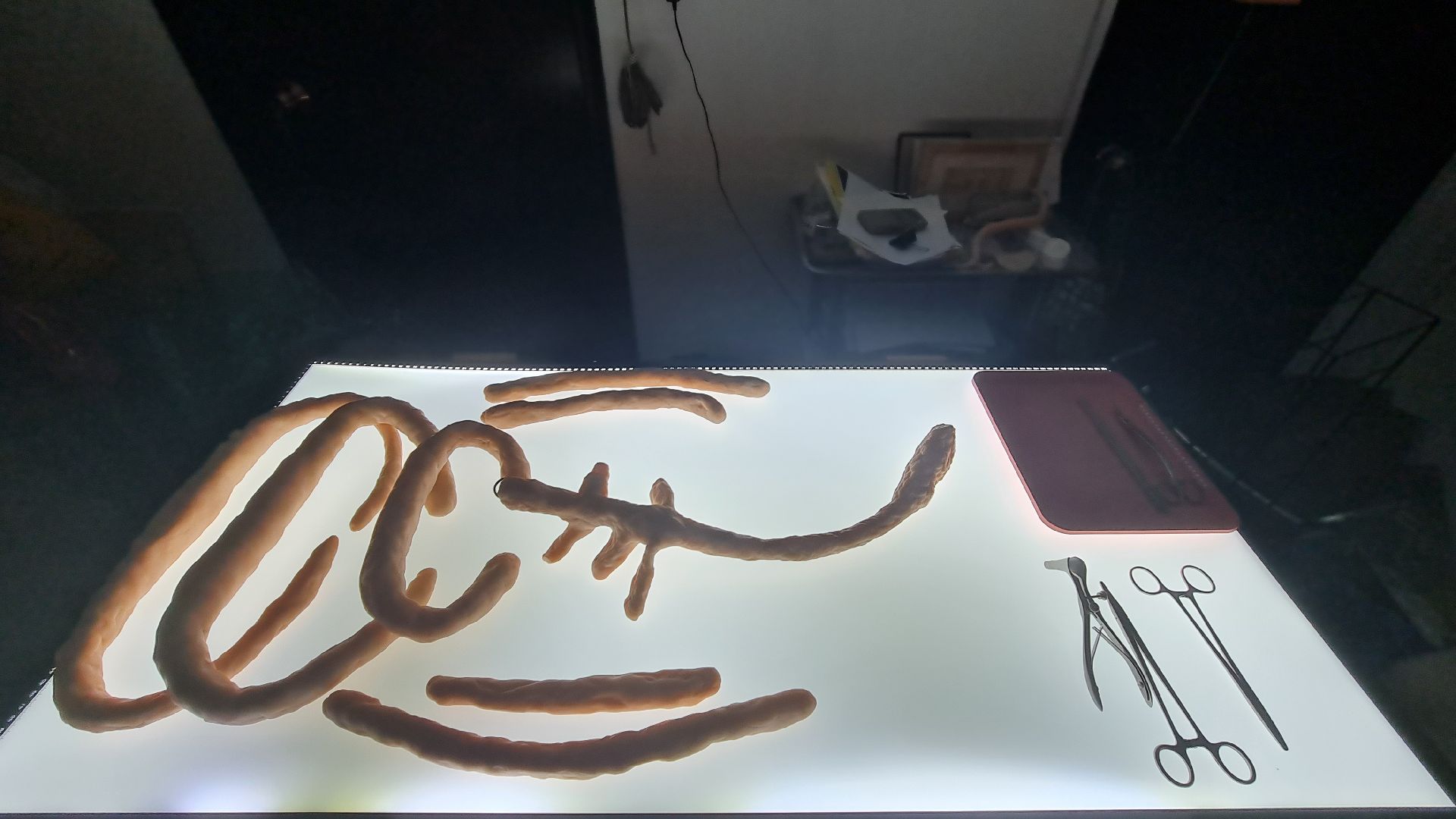

Polymer sculptures, lightbox prints, lightbox, steel table, HD video with sound (07:16)

Dimensions

Dimensions variable

A whispering of salt

Year

2021 – 22

Medium

Polymer sculptures, lightbox prints, lightbox, steel table, HD video with sound (07:16)

Dimensions

Dimensions variable

This video installation uses abstracted representations and descriptions of the body as a basis to explore interweaving themes of gossip, melancholy, and narration. It posits an unnamed individual as the subject of an autopsy—a process to determine the cause of demise—as inspired by various ‘true crime’ forensic TV series. In such scenes, speculative, faux-scientific articulations are often framed as fact, yet are also interspersed with personal, even poetic observations that further plot and characterisation.

With this narrative structure as a framework, the viewer is presented with an unofficial, poignant account of its anonymous subject’s life and death. From corporeal abstractions that imply rather than accurately depict the body, to lyrical descriptions that transform the meanings of the analytical statements that preceded them, this work is deliberately open-ended in its attempts to approximate the subject’s identity and experiences.

With this narrative structure as a framework, the viewer is presented with an unofficial, poignant account of its anonymous subject’s life and death. From corporeal abstractions that imply rather than accurately depict the body, to lyrical descriptions that transform the meanings of the analytical statements that preceded them, this work is deliberately open-ended in its attempts to approximate the subject’s identity and experiences.

Interview with the artist

Q Curators

Your recent body of work deals with fleshy, abstracted figurations, as compared to more literal depictions of people. What led you to explore such visceral forms?

The explorations started for a solo with Yavuz Gallery, for which I wanted to talk about the experience of coming out without the use of words. I was interested in thinking about forms that could hint at queerness, and began to combine natural objects with textures. In my later explorations, I became quite obsessed with the concept of “queer inhumanisms”1, exemplified by the works of Chicana lesbian photographer Laura Aguilar, who photographed her own body nude amidst natural settings. It was from there that I started thinking more deeply about ideas of bodies, cities, and landscapes (something which I had already delved into in a 2016 video work that looked at the body as an allegorical mountain).

The use and discovery of polymer clay, a material usually associated with doll-making, further added to this aspect of my work. I see the sculptures as representations of the desires of a child growing up in a heteronormative world, who had to disavow the so-called ‘feminine’ activity of playing with dolls.

1 ‘The encounter with the inhuman expands the term queer past its conventional resonance as a container for human sexual nonnormativities, forcing us to ask, once again, what “sex” and “gender” might look like apart from the anthropocentric forms with which we have become perhaps too familiar.’ Dana Luciano and Mel Y. Chen, “Has the Queer Ever Been Human?”, GLQ 21, no. 2-3 (2015): 189, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2843215.

The use and discovery of polymer clay, a material usually associated with doll-making, further added to this aspect of my work. I see the sculptures as representations of the desires of a child growing up in a heteronormative world, who had to disavow the so-called ‘feminine’ activity of playing with dolls.

1 ‘The encounter with the inhuman expands the term queer past its conventional resonance as a container for human sexual nonnormativities, forcing us to ask, once again, what “sex” and “gender” might look like apart from the anthropocentric forms with which we have become perhaps too familiar.’ Dana Luciano and Mel Y. Chen, “Has the Queer Ever Been Human?”, GLQ 21, no. 2-3 (2015): 189, https://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-2843215.

A whispering of salt was specifically inspired by the autopsy scenes seen in crime procedural television shows. Why were you drawn to the ‘forensic’ as a motif in this work?

In my early 20s, I made the choice to study Chemistry and Biological Chemistry for my first degree. During that period, I ignored my own dreams of pursuing something in the arts, and wanted to focus on forensic science. I started watching a lot of television shows in which forensic techniques were used to solve crimes, including Bones. I was particularly drawn to this show because the main character, a forensic anthropologist named Temperance Brennan, was portrayed as someone who was tactless and hyper-rational. I grew up as quite an emotional and sensitive person, and she represented the type of person I wanted to be at the time, so somehow I started mimicking her mannerisms and personality.

As I moved on from that phase of my life and began developing my art practice, I forgot about this obsession of mine. But during the lockdown period of the pandemic, I revisited Bones again. While I found myself questioning the accuracy of the various laboratory procedures, I still enjoyed the narrative arc the series had. I also saw something poetic and poignant in the way the autopsy scenes played out. I had never performed an autopsy during my earlier studies, so when the opportunity to ‘perform’ one in my artwork presented itself, I jumped on it.

As I moved on from that phase of my life and began developing my art practice, I forgot about this obsession of mine. But during the lockdown period of the pandemic, I revisited Bones again. While I found myself questioning the accuracy of the various laboratory procedures, I still enjoyed the narrative arc the series had. I also saw something poetic and poignant in the way the autopsy scenes played out. I had never performed an autopsy during my earlier studies, so when the opportunity to ‘perform’ one in my artwork presented itself, I jumped on it.

Your works often have a strong narrative, and even performative element. Why is this framing important to you?

Perhaps because of my own background in theatre, I’ve always enjoyed storytelling. I recall that when I was teaching ‘A’ Level Chemistry as part of an internship at Millennia Institute, I developed storylines for students to help them remember various pieces of information. This was a tool I had used in my own studies to make it a lot more fun—when I was studying organic chemistry synthesis, I always made little comics as a means to recall the terms and actions. In my artwork, I find combining various tangents into an arc to be a good creative exercise, and I hope this arc becomes something audiences can bring away with them.

Biography