This essay is one of three texts commissioned for this exhibition, discussing ‘bad imitations’ in disciplines beyond visual art.

When I was six, I stole three Little Bobdog rubber stamps from Popular Bookstore. They were barely bigger than pebbles, safely balled in my right fist inside the pocket of my pink nylon jacket as I made my way out of the premises. The harsh lights accentuated the juvenile thrill, blurring my vision of the shelves of model test papers promising academic excellence and a bright future. I transported my contraband unceremoniously across the threshold, then spent the rest of the day making imprint after imprint of this cartoon dog in various states of activity onto the pages of an old exercise book, each incrementally less clear than the one before, as the light outside faded. My parents came home, none the wiser of their little thief in canvas shoes sleeping soundly in Marine Parade. Later they divorced, leaving me as one of the last vestiges of their short-lived life together—indelible, blurry.

In 2019, I staged a play titled ANGKAT: A Definitive, Alternative, Reclaimed Narrative of a Native. 2019 was the year of the Bicentennial, marking 200 years since Sir Stamford Raffles first stepped foot on Singapore. It was also a year in which many in the arts wanted to present their own take on coloniality, and dig deeper into the island’s longer and richer 700-year history. The elevator pitch for ANGKAT was that it was a Malay version of the Singapore Story, but bastardised and rendered nonsensical. (Part of the premise of the play was the very real possibility of a Malay person winning the reality competition Singapore Idol again, and how that would tear the delicate fabric of racial harmony.) Humour was a way through which many people accessed the work, though it also concealed a deeper pain and visceral sadness related to what we think of as ‘national history’. At the same time, the play was also deeply personal—a corrupted download of what it is like to be Malay in this country—and it was riddled with references that were illegible. The title alone represented an impossibility, a challenge.

In 2019, I staged a play titled ANGKAT: A Definitive, Alternative, Reclaimed Narrative of a Native. 2019 was the year of the Bicentennial, marking 200 years since Sir Stamford Raffles first stepped foot on Singapore. It was also a year in which many in the arts wanted to present their own take on coloniality, and dig deeper into the island’s longer and richer 700-year history. The elevator pitch for ANGKAT was that it was a Malay version of the Singapore Story, but bastardised and rendered nonsensical. (Part of the premise of the play was the very real possibility of a Malay person winning the reality competition Singapore Idol again, and how that would tear the delicate fabric of racial harmony.) Humour was a way through which many people accessed the work, though it also concealed a deeper pain and visceral sadness related to what we think of as ‘national history’. At the same time, the play was also deeply personal—a corrupted download of what it is like to be Malay in this country—and it was riddled with references that were illegible. The title alone represented an impossibility, a challenge.

Production photo of ANGKAT (2019).

Courtesy of MonoSpectrum Photography.

It’s rare to be able to revisit a play. ANGKAT was staged as part of the 2019 M1 Singapore Fringe Festival, temporally bound within the festival period. Like all live performances, it existed in real-time in its time, sharing space with its audience in a theatre, the relationship and the energy exchange transient, yet mutually sustaining. Yet in the last three years I’ve found myself being asked to speak about the work post-performance, answering questions and giving presentations—almost as a postscript, an extension of the original performance event. It’s a chance to relook at the production, see it anew in relation to my initial ideas, and interrogate these ideas further. Perhaps it is a grasp towards articulating my (admittedly messy) process. This becomes especially clear when I attempt to remove the gloss of ‘the Bicentennial play’. ANGKAT was a play written by a myopic magpie, an assemblage of various ideas, images, inspirations from the past thirty-odd years, thrown together on a wall and then dared to stick.

The protagonist of the play is named Salma Abdullah. She is a mash-up of various tropes in Singapore Malay history, both real and imagined. On one hand, she is a modern, Malay woman, who loves the Spice Girls and their message of liberation as much as Awie and co. of the popular jiwang (slow rock) music. She is a contemporary take on Saloma, the iconic actor and singer from 1950s – 1960s Singapore, who had a voice described as lemak merdu (sweet and rich), and who, often pictured in a figure-hugging kebaya, was a symbol of Malay sensuality. And yet, Salma’s Malayness is complexified by the fact that she is born to British parents but adopted by a Singaporean Malay woman (the angkat in the title comes from the term anak angkat or adopted child). Sitting in the uncanny valley between foreign and local, or colonial and native, she is doubly exoticised, becoming both poster girl and an enemy of the people.

The protagonist of the play is named Salma Abdullah. She is a mash-up of various tropes in Singapore Malay history, both real and imagined. On one hand, she is a modern, Malay woman, who loves the Spice Girls and their message of liberation as much as Awie and co. of the popular jiwang (slow rock) music. She is a contemporary take on Saloma, the iconic actor and singer from 1950s – 1960s Singapore, who had a voice described as lemak merdu (sweet and rich), and who, often pictured in a figure-hugging kebaya, was a symbol of Malay sensuality. And yet, Salma’s Malayness is complexified by the fact that she is born to British parents but adopted by a Singaporean Malay woman (the angkat in the title comes from the term anak angkat or adopted child). Sitting in the uncanny valley between foreign and local, or colonial and native, she is doubly exoticised, becoming both poster girl and an enemy of the people.

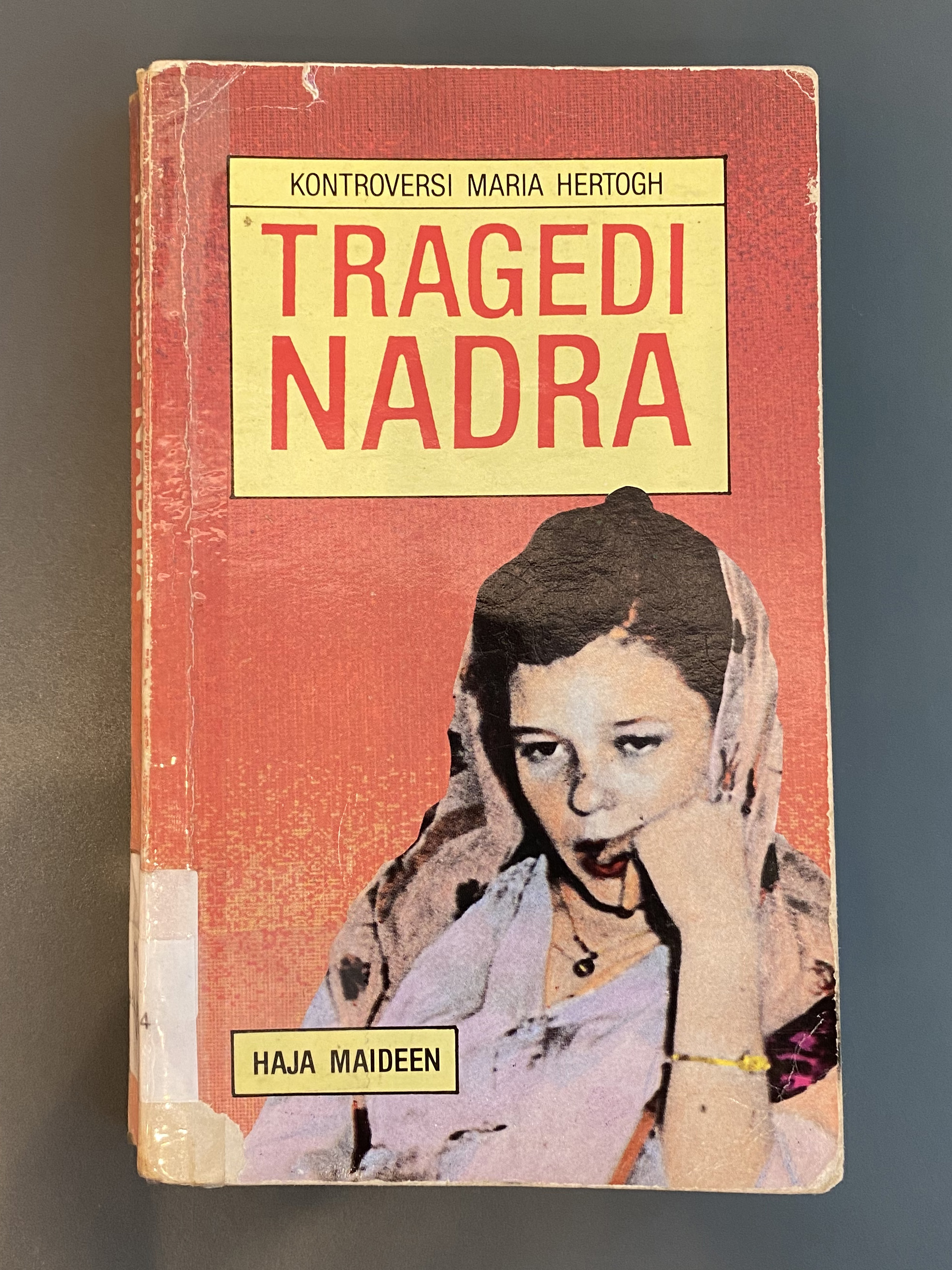

Book cover of Tragedi Nadra: Kontroversi Maria Hertogh by Haja Maideen. Courtesy of Nabilah Said.

Publicity image of ANGKAT. Courtesy of Erfendi Dhahlan.

Publicity image of ANGKAT. Courtesy of Erfendi Dhahlan.

The racial elements of the storyline, and a plot line involving a flawed voting process also allowed me to render her as two other iconic figures. The first is Maria Hertogh or Nadra, the Dutch child whose story of adoption by a Malay woman and the ensuing custody battle divided the nation, leading to riots in 1950. The spectre of the riots is often revisited by the Singapore state as a lesson about racial and religious harmony, and to some extent, about colonial incompetency. The second is President Halimah Yacob, who in 2017 became Singapore’s first female president, as well as the first Malay president in forty-seven years following the unprecedented ‘reserved’ presidential election requiring all candidates to be Malay. President Halimah’s Malayness is sometimes questioned because her father is said to be Indian—but this racial framing is only significant because the election itself was racialised. I asked Shafiqhah Efandi, the actor playing Salma, to pose like these figures in publicity shots, and renderings of these various characters could be seen in different parts of the play. The net effect is that audiences ended up not quite knowing the “real” Salma. In fact, her voice is “stolen” from her in multiple ways—she is often spoken about in third person, and is literally taught what to say. In an audition, she is told: “We’ll tell you when we want you to sing.”

Production photo of ANGKAT (2019). Courtesy of MonoSpectrum Photography.

Still from Bujang Lapok (1957). [Source]

Still from Bujang Lapok (1957). [Source]

ANGKAT was a palimpsest of cultural touchstones I hazily remember, growing up on a diet of old Malay movies, TV3 (read as “Tivi Tiga”), and ‘90s radio DJs bantering with makciks on air. The three omnipresent boys in the play, named Budak 1, Budak 2 and Budak 3, were canvases onto which I could map iconic Malay character types. Most obviously, I referenced the 1950s – 1970s Bujang Lapok trio of P. Ramlee, Aziz Sattar and S. Shamsuddin, and their attempts at finding love and success. These movies were often musical, which offered a sense of escapism for the characters of ANGKAT to latch onto. In one scene, the three boys play punk rockers who burst out into the classic Malay rock hit Isabella by the band Search. I think not many recognised the influence of the 1990 movie Fenomena here, in which actor Ramona Rahman plays a British woman who meets a rock group led by real-life rocker Amy Search. I also tapped on Shafiqhah Efandi’s natural singing ability in one of the scenes in the play, where she serenades the audience with a version of Singapura Waktu Malam, a song Saloma sings in the movie Labu Dan Labi (1962).

Saloma singing in Labu Dan Labi (1962)

[Source]

[Source]

Shafiqhah Efandi singing as ‘Salma’. Production video of Angkat (2019) by Eric Lee.

Music and singing was also a way to explore deeper emotions that the characters could not easily express. This was exemplified by the references to the hyper-emotive Malay music genre, jiwang, and Bani Haykal’s quietly unsettling sound design. Used in this way, music was often the gateway to creating a discordant mood in the play, turning something fun and enjoyable into internalised, and then externalised pain.

Melancholy Without Hope by Bani Haykal, from ANGKAT (2019). Courtesy of Bani Haykal.

BUDAK 3: Why don’t you use your tears? Can’t you cry? Is it all dried up?

BUDAK 2: You can always cry on the inside. Just swallow it up!

BUDAK 3: If not, you can try crying aloud! Like karaoke. Sing out loud, like you’re at a wedding.

Excerpt from ANGKAT (2019), translated to English

In trying to challenge the assumptions of an official history of Singapore, I might have—partly by accident and partly by design—overcorrected. If I could not re-present, perhaps I would distort. This was interesting, as an important element of conventional dramatic performance is that of mimesis, of making a copy or representation of reality that strives towards perfection. In art, students are often trained to learn from a master—and indeed, the way in which the formal learning of art has been transmitted has always been in service of something or someone superior, orientated towards the west. In the context of ANGKAT, what was perfection? As an act against the Bicentennial-as-national-project, it seemed apt to rage against the conventions of idealised representation. Hence, the bastardisation: Salma also appears in the play as Singa, an immigration officer who is a cross between a sinister Merlion and a cartoony Courtesy Lion, dispensing advice like bitter medicine.

Top left: Production photo of ANGKAT (2019). Courtesy of MonoSpectrum Photography.

Top right: Singa the Courtesy Lion. Courtesy of Khairullah Rahim.

Bottom left: Merlion Park at the Marina Bay waterfront.

Bottom right: The Sentosa Merlion at night. Courtesy of Felicia Low-Jimenez.

Top right: Singa the Courtesy Lion. Courtesy of Khairullah Rahim.

Bottom left: Merlion Park at the Marina Bay waterfront.

Bottom right: The Sentosa Merlion at night. Courtesy of Felicia Low-Jimenez.

To create the unfaithful translation, the imperfect copy, is to not give any easy answers. The audience has to work harder to understand the play’s multiple meanings. In the production, director Noor Effendy Ibrahim asked Shafiqhah (who does not look Caucasian like her character is meant to be, or like Maria Hertogh was) to speak both Malay and English with a British accent. This defamiliarisation was a clue to understanding the work—not as comedic choice, but a key to its making/unmaking. And yet, in revisiting this work, I realise the impossibility of these moments of intervisuality, when the work experienced is as ephemeral as theatre wonderfully is. These twinned, tripled, quadrupled images are at best suggested, never shown (adhering to the writing adage of “show, don’t tell”), and depended on the audience to decode them based on their own lived experiences, or lack thereof.

Unsurprisingly, the dense imagery and writing in ANGKAT was impenetrable to some. As a writer who also identifies as a critic, I have to make peace with that. The audience completes a work, and subjective and multiple readings of a production is par for the course. Perhaps it is a kind of failure when a maker is asked again and again to speak about a work that was, in its first instance, indelible, blurry. I could easily crumble and take this as a personal failing, but I think this refusal to do so is also important. As artists, we often own our vulnerability when making art, but harden when it comes to the examination of it. This text is perhaps like a softening. Or to borrow the words of Kuo Pao Kun, a recognition of a worthy failure. One that flies in the face of the accepted success story formulas we are used to hearing in “Third World to First” Singapore.

Failure, if difficult for the ego of the playwright, can be inherently more interesting—what does this say about the play, its audience, its country, its people? Denseness, for example, requires labour to unpack. The density in ANGKAT, and the labour required to process it, can be seen as a reverse engineering of a kind of indefatigable, tireless processing of meanings that minorities do every day in Singapore—not just through reading what is, but also through reading, re-reading, and over-reading what was and what should be. It is to process the play through the lens of pain. In that act of code-switching, we are laughing; in that song we’re singing, we are crying; in that last banal moment, we are dying.

Unsurprisingly, the dense imagery and writing in ANGKAT was impenetrable to some. As a writer who also identifies as a critic, I have to make peace with that. The audience completes a work, and subjective and multiple readings of a production is par for the course. Perhaps it is a kind of failure when a maker is asked again and again to speak about a work that was, in its first instance, indelible, blurry. I could easily crumble and take this as a personal failing, but I think this refusal to do so is also important. As artists, we often own our vulnerability when making art, but harden when it comes to the examination of it. This text is perhaps like a softening. Or to borrow the words of Kuo Pao Kun, a recognition of a worthy failure. One that flies in the face of the accepted success story formulas we are used to hearing in “Third World to First” Singapore.

Failure, if difficult for the ego of the playwright, can be inherently more interesting—what does this say about the play, its audience, its country, its people? Denseness, for example, requires labour to unpack. The density in ANGKAT, and the labour required to process it, can be seen as a reverse engineering of a kind of indefatigable, tireless processing of meanings that minorities do every day in Singapore—not just through reading what is, but also through reading, re-reading, and over-reading what was and what should be. It is to process the play through the lens of pain. In that act of code-switching, we are laughing; in that song we’re singing, we are crying; in that last banal moment, we are dying.

Production photos of ANGKAT (2019). Courtesy of MonoSpectrum Photography.

I remember seeing a Caucasian person fall asleep for the most part of the show on one of the nights, and thought to myself that it was an apt metaphor. If the colonial perspective was once accepted as dominant, universal, transmissible, what does it mean for the native’s story to be haphazard, oddly specific, insular? But like trying to explain a fever dream, more and more I’ve realised that the bounds of the play made it an imperfect vehicle for my thoughts, a fragile bubble that collapses upon meeting with the demands of logical or narrative comprehension. (The play tried to hew to a structure, but barely so, with disconnected storylines, time jumps, characters who died and reappeared as ghosts the next minute, etc.) More than an essay about bad imitation, perhaps this is also an attempt to reanimate the detritus of ANGKAT, in search of a new comprehension.

MAK: Why do you keep wanting to start again?

SALMA: Because I want to... I want to get our story right.

MAK: But our stories started out disconnected. You can’t make it magically connect.

SALMA: We have to try.

Excerpt from ANGKAT (2019), translated to English

As a final coda, I think of the six-year-old in Marine Parade excited by a petty transgression. I think of stamping as an act of liberation, and the inevitability of disappointment as a minority in Singapore. I think of feet buried in reclaimed sand that continually recede but never seem to wash away. I think of loneliness. I think of regret. I hold all these images like pebbles in my hand, as explanations of the past and possible interpretations of the future. I offer them, palms up, to be examined once again, long after the ink runs dry and the theatre fades to black.

Biography

Nabilah Said is a playwright whose works explore history, memory, and shifting communities. ANGKAT (2019) won Best Original Script at the 2020 Life Theatre Awards, and is an official text of the National University of Singapore’s Singapore English Language Theatre module. Her play Inside Voices (2019) won the Outstanding New Work award at London’s VAULT Festival, and was published by Nick Hern Books UK. She has worked with companies such as Teater Ekamatra and The Necessary Stage, and is the founder of collectives Main Tulis Group and Rupa co.lab. Other recent works include audiovisual trail Lost & Found: Serangoon (2021). Nabilah was a former Straits Times arts correspondent, and is currently the editor of Southeast Asian arts publication ArtsEquator.